King changed my daughter’s nation

IN KING’S FOOTSTEPS

Cy nthia Tucker is a former editorial page editor of the Journal- Constitution and winner of the Pulit zer Prize for commentary.

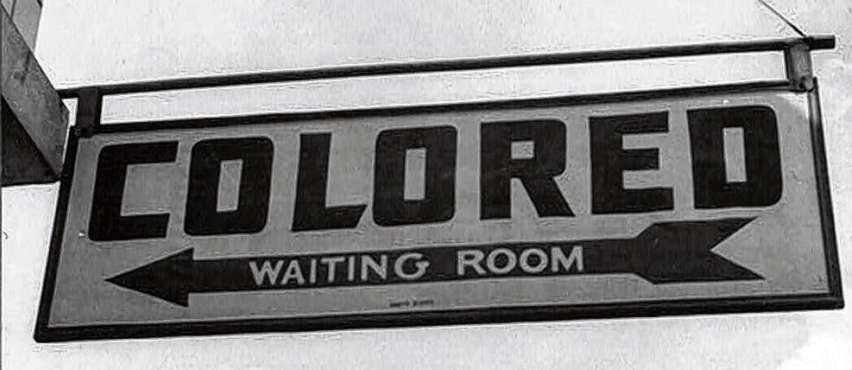

A sign at the Greyhound bus station in Rome, Ga., in 1943 speaks of a different America. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

A few years ago, I took my young daughter to the High Museum of Art to see an exhibition of photo graphs titled “Gordon Parks: Segregation Story.” I wanted Carly, 5 at the time, to begin to understand that central pillar of the history of her country.

Alongside works by the legendary Parks, the High featured some black-and white images by documentary photographer Leonard Freed.

Carly stared at one shot just outside a segregated waiting room, with a large “colored” sign swinging over the entrance.

“Mommy, what’s that word?” she asked.

“Colored,” I said.

By then, she knew all her colors, and she could make no sense of it.

“Colored how?” she asked.

It was a fraught moment, heavy with her innocence and my awkward and halting efforts to teach her something of a recent past that she could not possibly comprehend.

Who could? How could anyone — child or adult — wrap his head around a political system whose laws dictated that black people and white people could not even pee in the same place? I struggled to explain Jim Crow to her, but her uncomprehending look showed me that I was failing. It took me a few days to come to the awareness that it was just as well, that my problem was a good one to have: She will grow up in such a different time and place that she simply cannot grasp what my small-town Alabama childhood was like.

Fifty years after the death of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., the nation has been irreversibly transformed in ways both subtle and overt. I think of that transformation every time one of Carly’s little blond pals leaves my house after a sleepover, or she is transfixed watching gymnast Simone Biles on television, or I see Lupita Nyong’o on the cover of a fashion magazine.

Carly was born in December 2008, just after the election of President Barack Obama. Surely, I thought, his victory was a symbol of King’s beloved community, of which King had spoken, a nation whose people were judged not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

In a diary I kept in the months after her arrival, I wrote with such giddy hopes for the nation in which she would grow up.

Since then, of course, my expectations have been tempered, my optimism curbed. The election of President Donald Trump — whose introduction to the political stage was as the birther-inchief denying Obama’s legitimacy — was evidence of a backlash by white voters who wanted to turn back the clock.

But those are the last gasps of a dying order, the ragged remnants of a losing army struggling for white hegemony. Half a century after King’s assassination, there is no going back.

That’s not to say that my child, and millions of children of darker hues, will never struggle with racism.

Systemic barriers remain, as do old-fashioned prejudices of the sort that are buried deep in the psyches of white police officers, teachers and store clerks — prejudices of which they are hardly aware. Black and brown children will still have to work harder and comport themselves with more discipline and finesse to be judged as good as their white peers.

Still, Carly will take for granted opportunities that I didn’t have and be afforded privileges that were routinely denied to black people when I was her age. She has already eaten in fine restaurants that would have denied service to my family when I was a child; she has stayed in hotels and motels that would have followed the customs of Jim Crow 50 years ago; she has attended schools that would have prohibited her entry.

By the time she was born, Disney had already released an animated feature with its first black princess, Tiana. While I found that celebratory enough that I bought the DVD — “The Princess and the Frog” — before I had a child, perhaps the more noteworthy difference between Carly’s history with movies and mine is the countless number of films she has already seen, including the recently released “Black Panther.”

(She is an easily frightened kid, but I judged that the positive cultural messages would outweigh the comic-book violence.

She loved the movie.) By contrast, I had only seen two or three movies by the time I finished high school. That’s because my parents tried to protect their children from the harsh lash of Jim Crow by forbidding us to patronize establishments that would not treat us with respect. Since black people were forced to sit upstairs in a dirty peanut gallery in my hometown’s lone movie theater, we simply didn’t go.

And there are other striking contrasts between Carly’s world and my own. Obama’s tenure coincided with the first eight years of her life, so she saw nothing exceptional about a black president.

She took it for granted that brown-skinned little girls, with hair like her own, would frolic on the White House lawn. And that may have been the most remarkable transformation of all.

Alongside works by the legendary Parks, the High featured some black-and white images by documentary photographer Leonard Freed.

Carly stared at one shot just outside a segregated waiting room, with a large “colored” sign swinging over the entrance.

“Mommy, what’s that word?” she asked.

“Colored,” I said.

By then, she knew all her colors, and she could make no sense of it.

“Colored how?” she asked.

It was a fraught moment, heavy with her innocence and my awkward and halting efforts to teach her something of a recent past that she could not possibly comprehend.

Who could? How could anyone — child or adult — wrap his head around a political system whose laws dictated that black people and white people could not even pee in the same place? I struggled to explain Jim Crow to her, but her uncomprehending look showed me that I was failing. It took me a few days to come to the awareness that it was just as well, that my problem was a good one to have: She will grow up in such a different time and place that she simply cannot grasp what my small-town Alabama childhood was like.

Fifty years after the death of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., the nation has been irreversibly transformed in ways both subtle and overt. I think of that transformation every time one of Carly’s little blond pals leaves my house after a sleepover, or she is transfixed watching gymnast Simone Biles on television, or I see Lupita Nyong’o on the cover of a fashion magazine.

Carly was born in December 2008, just after the election of President Barack Obama. Surely, I thought, his victory was a symbol of King’s beloved community, of which King had spoken, a nation whose people were judged not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

In a diary I kept in the months after her arrival, I wrote with such giddy hopes for the nation in which she would grow up.

Since then, of course, my expectations have been tempered, my optimism curbed. The election of President Donald Trump — whose introduction to the political stage was as the birther-inchief denying Obama’s legitimacy — was evidence of a backlash by white voters who wanted to turn back the clock.

But those are the last gasps of a dying order, the ragged remnants of a losing army struggling for white hegemony. Half a century after King’s assassination, there is no going back.

That’s not to say that my child, and millions of children of darker hues, will never struggle with racism.

Systemic barriers remain, as do old-fashioned prejudices of the sort that are buried deep in the psyches of white police officers, teachers and store clerks — prejudices of which they are hardly aware. Black and brown children will still have to work harder and comport themselves with more discipline and finesse to be judged as good as their white peers.

Still, Carly will take for granted opportunities that I didn’t have and be afforded privileges that were routinely denied to black people when I was her age. She has already eaten in fine restaurants that would have denied service to my family when I was a child; she has stayed in hotels and motels that would have followed the customs of Jim Crow 50 years ago; she has attended schools that would have prohibited her entry.

By the time she was born, Disney had already released an animated feature with its first black princess, Tiana. While I found that celebratory enough that I bought the DVD — “The Princess and the Frog” — before I had a child, perhaps the more noteworthy difference between Carly’s history with movies and mine is the countless number of films she has already seen, including the recently released “Black Panther.”

(She is an easily frightened kid, but I judged that the positive cultural messages would outweigh the comic-book violence.

She loved the movie.) By contrast, I had only seen two or three movies by the time I finished high school. That’s because my parents tried to protect their children from the harsh lash of Jim Crow by forbidding us to patronize establishments that would not treat us with respect. Since black people were forced to sit upstairs in a dirty peanut gallery in my hometown’s lone movie theater, we simply didn’t go.

And there are other striking contrasts between Carly’s world and my own. Obama’s tenure coincided with the first eight years of her life, so she saw nothing exceptional about a black president.

She took it for granted that brown-skinned little girls, with hair like her own, would frolic on the White House lawn. And that may have been the most remarkable transformation of all.