COURTESY OF RON WITHERSPOON

VISUAL ARTS ‘CLOTH PAINTINGS’

It is hard to find softness in the quilts of Dawn Williams Boyd.

There is flannel and silk. There are whispers of organza and jaunty grids of gingham. There is also a river of blood, hoods of Klansmen, and moonlight glinting off the hood of an assassin’s car.

Which is why, looking through the virtual exhibition of the Atlanta artist’s new show “Cloth Paintings” at Fort Gansevoort Gallery in New York City, the portrait quilt “Peaches and Evangeline” stands out. Two young women lean against the bulbous curves of a 1940s car. One casually bends her elbow on the edge of an open window; the other mimics the gesture. Smiles light their brown faces, implying a loved one might be taking their picture. They may not even be adults yet given their pinnedup ponytails. Boyd has dressed them in the innocence of florals, eyelet and ribbon.

Without a written narrative, it is almost pretty in a way that is nostalgic, maybe even saccharine.

But Annie Roselea “Peaches”

Moore and her sister, Evangeline were the daughters of Harry and Harriette Moore, two central Florida educators and civil rights workers blown up — authorities believed but never proved — by white supremacists. Dynamite was planted under their bedroom on Christmas Day 1951, their wedding anniversary. Harry died within moments, Harriette, days later from internal injuries.

“I have not done any ‘pretty’ work,” Boyd said in late September from her Atlanta home. “All the pieces are political pieces, a rendition of historical fact.”

It is in this historic moment of extreme polarization along class and political lines, and amid calls from Black people for accountability in institutions from law enforcement to high education to the arts, that Boyd’s work is finding a new audience. “Cloth Paintings” pulls largely from her textile work over the past four years, amplifying themes of race, freedom of speech, mass incarceration and economic injustice.

A few images in the show are pulled from her latest series, “The Trump Era,” a commentary on the documented rise in white supremacists' activity and racial division in the nation.

Take “Racism No Longer has the Decency to Hide Its Face.”

Unlike “Peaches and Evangeline,” it is blunt force: Ku Klux Klan members, in hoods but no masks, march in front of the White House. Lucifer is among them, styled as a black-robed Grand Dragon. His skin is as red as the Confederate and Nazi flags held aloft by his compatriots.

In “Trump’s America,” the lower half of the flag is rendered in shades of red and blue cotton, a great diversity of tone punctuated by crisp white stars. Boyd said it harks back to pre-2016 representing “what we were. A blend of races, sexualities, people.”

The upper half of the quilt is stark, rendered in shades of white, beige, and ivory, almost monochrome save for red stitching, barely visible, seeping from the corners of the stars. There is no middle ground between top and bottom, what was and what is. The flag is displayed upside down. To some that is an act of desecration, for others a signal of danger and distress.

“All quilts tell a story based on the intent of the maker, even a patchwork quilt” said Carolyn Mazloomi, a National Endowment for the Arts Heritage Fellow, curator and one of the nation’s leading experts on African American quilting history. “Social justice quilts are a soft way to talk about difficult subjects, and Dawn is a master story teller. I’ve shown her work for about 15 years. She digs deep in terms of her subject matter.”

“Historically Charged”

Boyd’s work has been exhibited by smaller Atlanta venues for years, from the Southwest Arts Center, where she had a solo show in 2017, to Hammonds House Museum, Callanwolde Fine Arts Center and, most recently, at Agnes Scott College. The 68-yearold’s work has also been part of group shows across Georgia as well as in France, California, New Mexico, Colorado, and Pennsylvania.

Fort Gansevoort founder Adam Shopkorn followed Boyd’s work from afar. But given the horror of George Floyd’s killing and the ugliness flowing through the 2020 presidential contest, this seemed the right time to show Boyd’s art particularly to a New York audience, said Sasha Bonét, curator of the Fort Gansevoort show. (The show is online only from now through Nov. 21).

The decision to showcase any racial justice art now could be considered opportunistic on the part of galleries or museums that have not regularly given space to Black artists in the past. Racial violence against Black people and its depiction by Black artists is age old. Presence of those testaments in the form of solo exhibitions or permanent collections are not. But Bonét, who is Black, said Fort Gansevoort was trying to honestly acknowledge the moment and what has led to it by choosing Boyd.

Bonét paired her own autobiographical text and a range of photos to show along with Boyd’s quilts. There are ones that speak to history, including one from the Centers for Disease Control of a clinician injecting a syringe needle into the arm of a Black man during the actual Tuskegee Experiment. There are also contemporary photos such as blood-stained or common place objects found in the apartment of Breonna Taylor after she was shot and killed in a police raid.

“Her work is so historically charged,” Bonét said. “I wouldn’t want it to be in front of the eyes of someone who wasn’t ready to see it and hear the message that was intended to be spread. She has such a clear intention."

“Eureka Moment”

That intention was set early. Boyd and her brother were reared in Atlanta, by educator parents. Her mother, Narvie Williams Puls was a Spelman College graduate and became a principal in Atlanta Public Schools with a keen interest in history.

When her mother wasn’t making paper dolls for her out of brown paper bags — so she would have toys that looked like her — she was helping Boyd’s grandmother sew dresses for Boyd. There were always scraps of fabric around.

Boyd’s father, John Williams was a high school athletic director. Both parents were concerned when their daughter declared she was going to major in art at Stephens College in Missouri.

But that path had been set years earlier at D’Youville High School in Atlanta where Boyd attended and learned she wasn’t good at math or Latin, but she had a talent for art.

“I told them what I wanted to be and they were concerned, but I was insistent that was what I wanted to do,” Boyd said.

Her first job out of college was coloring maps to indicate race, income and other markers for the Atlanta Regional Commission. A marriage to her first husband took her to Denver, Colorado, where she spent the next 29 years working in reservations for United Airlines, raising her children and painting in her off hours. She helped found two Black arts organizations there that regularly sponsored arts festivals and public art installations by Black and Latino artists. She kept painting, primarily acrylics on plywood or corrugated cardboard.

Boyd recalls giving a talk at a local Denver college about the important story quilts of Faith Ringgold, one of the 20th century’s most celebrated textile artists and painters. Doing research in preparation, Boyd saw where Ringgold’s practice of painting a piece then stitching it to a canvas, could be a way forward in her own work.

“That was a eureka moment for me,” Boyd said.

“Why not just make the entire image out of fabric?”

She taught herself to embroider from reading library books. It wasn’t until she took early retirement and moved back to Atlanta in 2010 with her second husband, Irvin Wheeler, that she was able to devote herself full time to textiles.

Her mother’s interest in history, particularly African history and Black history (her mother founded the Omenala Griot Afrocentric Museum in the West End) was a seed that blossomed in Boyd upon her return to her hometown. Creating the quilt “Bad Blood: Tuskegee Syphilis Experiments, Macon County, AL 1932-1972,” she needed flannel for the suit jackets of some of the pall bearers carrying the open pine casket of a victim of the infamous government experiments on the effects of venereal disease on Black men. For others she needed denim because, “for some of the men, their Sunday best may have been a clean pair of overalls,” Boyd said. She also needed burlap, blue wool and denim.

The body is wrapped in a burlap shroud as it would have been back then for an indigent victim. A nurse, who cared for some of the men, wears blue anemone on her uniform, the flower of forsakenness and sickness. Each tiny petal is rendered individually.

“When I was a painter, I was spending so much time pouring over paints in the art supply store, now I spend my time fingering fabrics and finding interesting patterns,”

Boyd said. Standing in a Tradition Contemporary textile artists such as Bisa Butler and legends such as Rosie Lee Tompkins of California, the quilters of Gee’s Bend, Alabama, and Jessie Telfair of Parrott, Georgia, are all part of a long line of African American women stretching back to Harriet Powers, enslaved near Athens in the mid-1800s, who became famous for her story quilts. Powers told Biblical tales. Boyd’s flag quilt brings to mind the spirit that inspired Telfair’s “Freedom” quilt in which the word “freedom” is repeated over and over in red and blue. Both are responses to injustice.

For Telfair, it was losing her job in a school cafeteria after she tried register to vote in the 1960s.

“This was an easy way for her to make a statement,”

Monica Obiniski, curator of decorative arts and design at the High Museum of Art said of Telfair.

The graphic quality of Boyd’s work shows she is “engaged in the moment we’re in and engaged in identity, politics, gender and race. Someone who is striving for social change.”

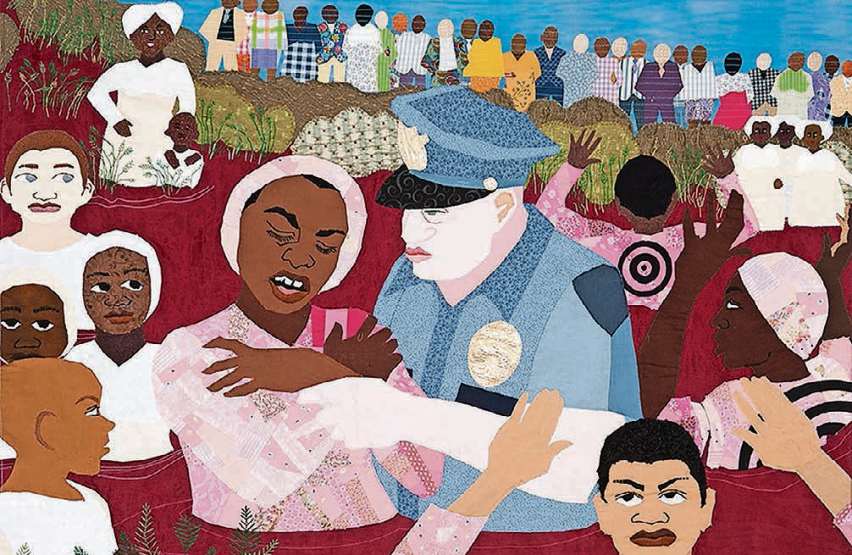

Boyd’s effort is literal. “Baptizing Our Children in a River of Blood” depicts a group of children being baptized in a thick stream of blood as parents both Black and white look on from the banks above, seemingly helpless to do anything.

A police officer officiates the ritual.

“I was thinking about the children who turn on the television and see Black men and women killed by police as a matter of course,” Boyd said.

“You can see it on your phone.

An entire generation of little kids who see this every day.

How is this going to affect Black and white children in how they grow up and how they see their place in the world? How will it affect their psychological make up?”

With each spot of lace, each square of linen, Boyd aims to make a ledger of this moment’s hard lessons.

VIRTUAL ART EXHIBITION “Cloth Paintings” by Dawn Williams Boyd Through Nov. 21.

Free. Online via Fort Gansevoort Gallery, New York, New York. www.fortgansevoort. com.

NOTE: Images in this exhibition may be disturbing or unsuitable for some viewers, especially children